See the strange creatures NOAA found at the bottom of the sea

Each year, the NOAA ship Okeanos Explorer maps an area of the seafloor the size of West Virginia.

When compared to the total Atlantic Ocean, which spans 41 million square miles, West Virginia’s not so large. But the discoveries the team is making are vast: Small creatures in hydrothermal vents. Asphalt volcanoes. Ancient landslides. New species of squid.

A brittle star climbs on top of an armored sea robin. Image courtesy of NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, Océano Profundo 2015: Exploring Puerto Rico’s Seamounts, Trenches, and Troughs

Last month, while traveling around Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands, the NOAA ship spotted 100 different species of fish, along with 50 different species of coral and hundreds of other invertebrates. One fish species is so new it’s never been named; another jellyfish-like creature called a ctenophore or comb jelly, has only been observed once before.

They also captured unusual behaviors, such as sea stars hunting prey, shrimp cleaning themselves and a hermit crab using an anemone as a shell.

The Okeanos Explorer came across this hermit crab using an anemone instead of a shell while exploring the Puerto Rico Trench. Image courtesy of NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, Océano Profundo 2015: Exploring Puerto Rico’s Seamounts, Trenches, and Troughs

It’s a common refrain among oceanographers: We know more about the surface of Mars than we do the bottom of the ocean. About 95 percent of the ocean remains unexplored. And to date, just 15 percent of the ocean floor has been mapped. The result is that the deep sea hosts many creatures that are unknown or not well understood to science. The scientists on Okeanos Explorer are working furiously to change that.

“It’s the last frontier,” says Mike Cheadle, associate professor of geophysics at the University of Wyoming. “The only way to see it is to go down there and do it.”

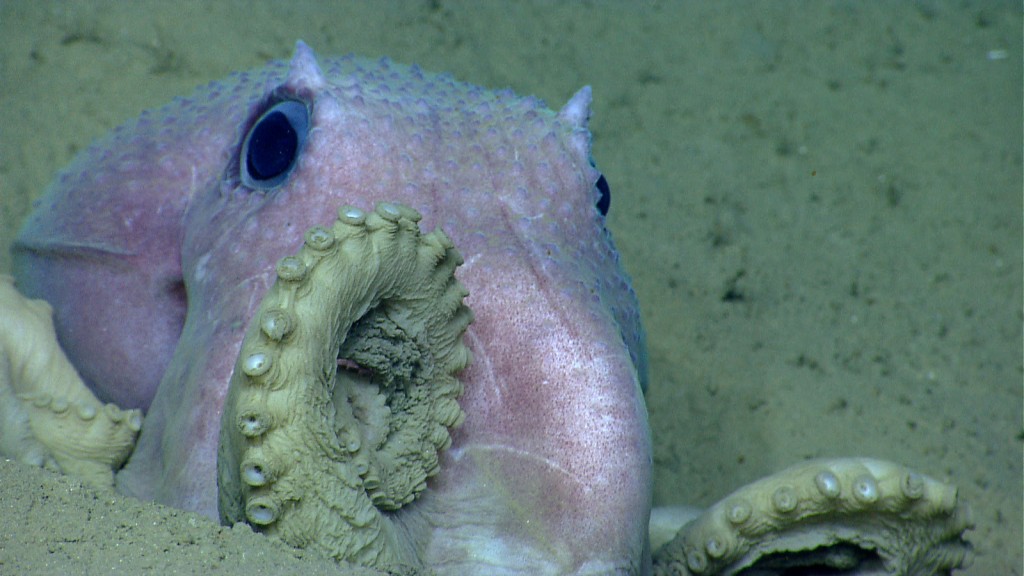

An octopus poses for the Okeanos Explorer’s cameras near Shallop Canyon off the Northeast U.S. in 2013. Image courtesy of NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, 2013 Northeast U.S. Canyons Expedition

But descending one to three miles underneath the ocean surface is a technical challenge. Satellites give scientists a rough outline of the ocean floor, but lack detail. And looking for marine life requires submersible vehicles that can withstand the pressure of a 19,000 foot dive, and those are expensive.

“Features start appearing ping by ping. It’s remarkable to watch the seafloor unfold before you.”

It’s a real dilemma for deep-sea scientists, Cheadle said: How do you start your research when you don’t know what’s down there?

Since it was commissioned in 2008, the Okeanos Explorer has sailed around the world with two goals: map the ocean floor and explore it with underwater cameras.

This jellyfish was spotted during the most recent mission on April 16. Image courtesy of NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, Gulf of Mexico 2014 Expedition

For mapping, the ship uses sonar with a resolution of 33 to 165 feet, depending on the depth, said Brian Kennedy, who coordinates Okeanos Explorer for NOAA’s Office of Ocean Exploration and Research. Each year, the expedition maps between 23,000 and 38,000 square miles of the ocean.

To Kennedy, the maps alone are an achievement.

“Features start appearing ping by ping,” he said. “It’s remarkable to watch the seafloor unfold before you. The data is amazingly exciting.”

But these sonar images only tell scientists so much. So after mapping an area, the ship sends down two submersible, remote-operated vehicles with cameras that livestream high-quality video of the ocean floor. Aboard the ship, a lead biologist and geologist act like film directors, guiding the cameras from one discovery to the next and narrating what they see for their online audience.

On a dive in the Gulf of Mexico in April 2014, the ship found small volcanoes that spewed asphalt along the ocean floor. The asphalt erupted into petal-like shapes. The crew named them “tar lilies.” Geologists watching the discovery on the livestream began calling in. On the video of the dive, you can hear their excitement.

ROV Deep Discoverer approaches the first “tar lily” on a dive in April 2014 in the Gulf of Mexico. The anemones living on and around the asphalt volcanoes indicated that the structures were anywhere from tens to hundreds of years old. Image courtesy of NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, Gulf of Mexico 2014 Expedition

“The great thing about today is we came down here thinking that these structures might be parts of a shipwreck. It’s pretty clear that they’re not now, that they’re naturally occurring,” said James Austin, the lead geologist aboard on the dive’s recording.

It’s worth pointing out Okeanos has spotted real shipwrecks too — this one in the Gulf of Mexico in 2012, for example. That discovery led to later expeditions, which uncovered two more ships.

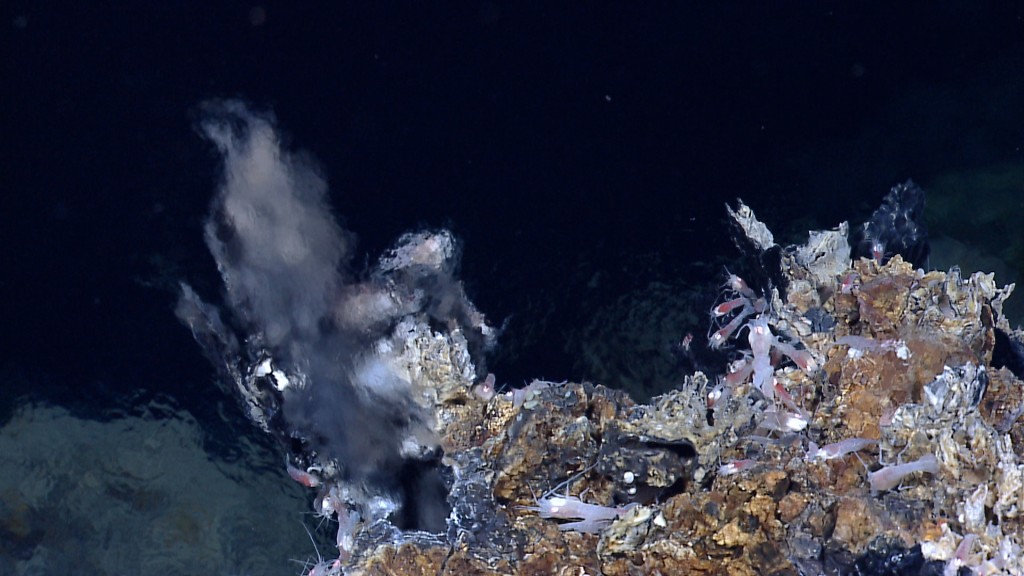

Other findings include new species in environments thought to be inhospitable. Cheadle recalls watching from shore when the ship’s cameras discovered hydrothermal vents along the Mid-Cayman Rise in 2011, complete with tiny critters.

“The water is 226 degrees Celsius (438 degrees Fahrenheit), and here are creatures unlike anything we see on the surface of the earth,” Cheadle said.

Hydrothermal shrimp and bacteria living near an active hydrothermal vent located southeast of the central Von Damm hydrothermal field in the Mid-Cayman Rise in 2011. Image courtesy of NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, MCR Expedition 2011

Brian Kennedy recalled seeing a new species of squid on his first Okeanos Explorer voyage near Indonesia. It had a narwhal-like horn protruding from its head and a long squid body. He watched the squid sink to the sea floor and use its horn to “hop”.

“We nicknamed it ‘Pogo squid.’ This was all novel to me,” he said. “That moment sticks with me, seeing this surreal Dr. Seussian creature.”

During an expedition, as many as 40 scientists ashore chime in daily with their thoughts and questions via a private instant messaging channel and phone line. Scientists capture screen grabs of animals and geologic features and email them to colleagues.

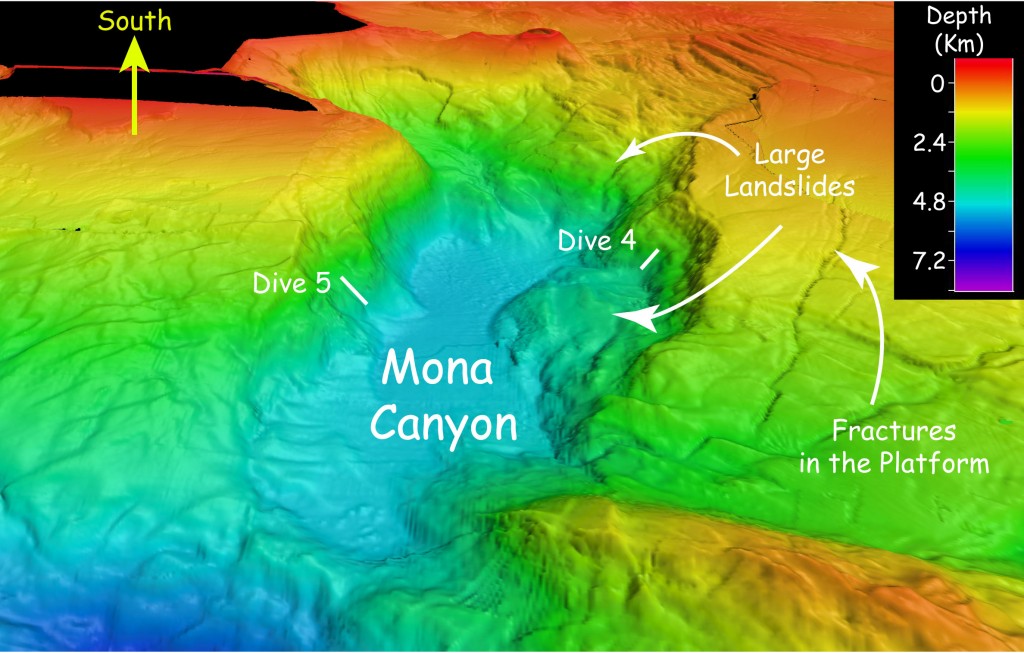

In the Mona Canyon off the coast of Puerto Rico, during the latest mission, the cameras spotted a sea star. From shore, Christopher Mah at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History called the ship. That sea star, he informed them, was incredibly rare. It hadn’t been seen since 1878.

This sea star, Laetmaster spectabilis, has not been recorded since it was initially described 130 years ago. The Okeanos recently found this sea star during a recent dive in the Caribbean. Image courtesy of NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, Océano Profundo 2015: Exploring Puerto Rico’s Seamounts, Trenches, and Troughs

“This is a great example of how little we have explored topographically complex and deep habitats, and how this telepresence technology allows us to connect with more scientists in real time,” Andrea Quattrini, a USGS postdoctoral researcher and lead biologist aboard the mission, wrote in an email.

Okeanos mapped an ancient landslide in the Mona Canyon off the coast of Puerto Rico in the spring of 2015. Scientists aren’t sure how old it is, but it could have been caused by an earthquake that generated a deadly tsunami in Puerto Rico in 1918. Image courtesy of NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, Oceano Profundo 2015

While the animals are known to steal the show on dives, the rocks on the sea floor have their own story to tell. In the Mona Canyon off the coast of Puerto Rico, the Okeanos Explorer found an ancient, enormous landslide — 9 miles wide and 6 miles long. When it occurred is unclear, but it could have been the result of a massive earthquake that caused the 1918 Puerto Rico tsunami, said Cheadle, the lead geologist on the dive. Geologists study ocean floor rocks and features to better underwater landslides or earthquakes, said Jason Chaytor, a USGS research geologist.

He points to the tubular rocks off the Northeast United States that the ship spotted in 2013.

“We just saw these amazingly weird features in the rock that we couldn’t understand,” Chaytor said. “They were just concentric tubular feature with an open aperture. To this day I still don’t know what they are.”

Throughout the dive, scientists narrate the expedition for the livestream audience. That part can be tedious on slow days, said Martha Nizinski, a research zoologist for NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service, who was on the Okeanos Explorer in 2013. But other times, it’s almost impossible to keep up with what’s unfolding on camera. One of her favorite moments: seeing undiscovered coral communities in deep canyons off of the Northeast United States.

“When I was out there in Heezen Canyon, we saw amazing corals all along the side of the canyon. We called it the coral forest,” she said. “That’s the beauty of this, going to areas where we don’t know anything…I think every time that the ship goes out, they find something we haven’t seen before.”

Correction: An earlier version of this post misidentified the location of the area of ocean floor that NOAA’s Okeanos Explorer maps each year. While the area mapped is equal to the size of West Virginia, the expeditions are not just limited to the North Atlantic, but occur throughout the world.

ncG1vNJzZmivp6x7sa7SZ6arn1%2Bjsri%2Fx6isq2ejmLamusKeZpynopa5brLOq5ysrKNiv6K%2BxGaqnpldqMGivtJmoKegkZe2tXnUp6qenZ5ivKSxwKdkn6SfpL8%3D